Charles Darwin's Autobiography

Edinburgh

|

|

| < | Famous Biologists | > |

|

| Old College, Edinburgh University, 1827 |

As I was doing no good at school, my father wisely took me away at a rather earlier age than usual, and sent me (Oct. 1825) to Edinburgh University with my brother, where I stayed for two years or sessions. My brother was completing his medical studies, though I do not believe he ever really intended to practise, and I was sent there to commence them. But soon after this period I became convinced from various small circumstances that my father would leave me property enough to subsist on with some comfort, though I never imagined that I should be so rich a man as I am; but my belief was sufficient to check any strenuous effort to learn medicine.

The instruction at Edinburgh was altogether by lectures, and these were intolerably dull, with the exception of those on chemistry by [Thomas Charles] Hope [1766–1844]; but to my mind there are no advantages and many disadvantages in lectures compared with reading. Dr. [Andrew] Duncan's lectures on Materia Medica at 8 o'clock on a winter's morning are something fearful to remember [In a letter written to his sister Caroline at the time, Darwin says"Dr. Duncan is so very learned that his wisdom has left no room for his sense, and he lectures, as I have already said, on the Materia Medica, which cannot be translated into any words expressive enough of its stupidity."].

|

|

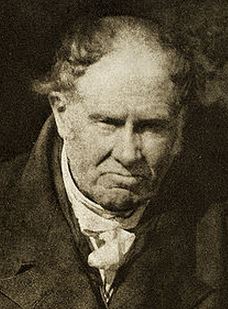

Alexander Munro (1773–1859) |

Dr. [Alexander] Munro [III (1773–1859] made his lectures on human anatomy as dull as he was himself, and the subject disgusted me [In the letter just mentioned, Darwin also comments about Munro:"I dislike him and his lectures so much that I cannot speak with decency about them"]. It has proved one of the greatest evils in my life that I was not urged to practise dissection, for I should soon have got over my disgust; and the practice would have been invaluable for all my future work. This has been an irremediable evil, as well as my incapacity to draw. I also attended regularly the clinical wards in the hospital. Some of the cases distressed me a good deal, and I still have vivid pictures before me of some of them; but I was not so foolish as to allow this to lessen my attendance. I cannot understand why this part of my medical course did not interest me in a greater degree; for during the summer before coming to Edinburgh I began attending some of the poor people, chiefly children and women in Shrewsbury: I wrote down as full an account as I could of the case with all the symptoms, and read them aloud to my father, who suggested further inquiries and advised me what medicines to give, which I made up myself. At one time I had at least a dozen patients, and I felt a keen interest in the work. My father, who was by far the best judge of character whom I ever knew, declared that I should make a successful physician, — meaning by this one who would get many patients. He maintained that the chief element of success was exciting confidence; but what he saw in me which convinced him that I should create confidence I know not. I also attended on two occasions the operating theatre in the hospital at Edinburgh, and saw two very bad operations, one on a child, but I rushed away before they were completed. Nor did I ever attend again, for hardly any inducement would have been strong enough to make me do so; this being long before the blessed days of chloroform. The two cases fairly haunted me for many a long year. [In the Life and Letters, Darwin mentions his belief that he inherited a dread of blood from his father:"His great success as a doctor was the more remarkable, as he told me that he at first hated his profession so much that if he had been sure of the smallest pittance, or if his father had given him any choice, nothing should have induced him to follow it. To the end of his life, the thought of an operation almost sickened him, and he could scarcely endure to see a person bled—a horror which he has transmitted to me—and I remember the horror which I felt as a schoolboy in reading about Pliny (I think) bleeding to death in a warm bath." (Actually, the elder Pliny died in a volcanic eruption and the nature of the younger Pliny's death is unknown. Perhaps Darwin was thinking of Seneca the Younger?)]

My brother stayed only one year at the University, so that during the second year I was left to my own resources; and this was an advantage, for I became well acquainted with several young men fond of natural science. One of these was [William Francis] Ainsworth [1807–1896], who afterwards published his travels in Assyria; he was a Wernerian geologist [i.e., a Neptunist], and knew a little about many subjects. Dr. [John] Coldstream was a very different young man, prim, formal, highly religious, and most kind-hearted; he afterwards published some good zoological articles. A third young man was Hardie, who would, I think, have made a good botanist, but died early in India. Lastly, Dr. [Robert Edmond] Grant, my senior by several years, but how I became acquainted with him I cannot remember; he published some first-rate zoological papers, but after coming to London as Professor in University College, he did nothing more in science, a fact which has always been inexplicable to me. I knew him well; he was dry and formal in manner, with much enthusiasm beneath this outer crust. He one day, when we were walking together, burst forth in high admiration of Lamarck and his views on evolution. I listened in silent astonishment, and as far as I can judge without any effect on my mind. I had previously read the 'Zoonomia' of my grandfather [Erasmus Darwin], in which similar views are maintained, but without producing any effect on me. Nevertheless it is probable that the hearing rather early in life such views maintained and praised may have favoured my upholding them under a different form in my 'Origin of Species.' At this time I admired greatly the 'Zoonomia;' but on reading it a second time after an interval of ten or fifteen years, I was much disappointed; the proportion of speculation being so large to the facts given.

Drs. Grant and Coldstream attended much to marine Zoology, and I often accompanied the former to collect animals in the tidal pools, which I dissected as well as I could. I also became friends with some of the Newhaven fishermen, and sometimes accompanied them when they trawled for oysters, and thus got many specimens. But from not having had any regular practice in dissection, and from possessing only a wretched microscope, my attempts were very poor. Nevertheless I made one interesting little discovery, and read, about the beginning of the year 1826, a short paper on the subject before the Plinian Society. This was that the so-called Flustra [a genus of the bryozoan suborder Flustrina] had the power of independent movement by means of cilia, and were in fact larvæ. In another short paper I showed that the little globular bodies which had been supposed to be the young state of Fucus loreus [a type of brown alga known by the common names Thongweed and Sea Spaghetti] were the egg-cases of the worm-like Pontobdella muricata [the skate-leech, a type of marine leech].

The Plinian Society was encouraged and, I believe, founded by Professor [Robert] Jameson [actually Jameson never attended the Plinian and was not its founder1; Jameson, who was Regius Professor at the University of Edinburgh for fifty years, founded the Wernerian Society, mentioned below]: it consisted of students and met in an underground room in the University for the sake of reading papers on natural science and discussing them. I used regularly to attend, and the meetings had a good effect on me in stimulating my zeal and giving me new congenial acquaintances. One evening a poor young man got up, and after stammering for a prodigious length of time, blushing crimson, he at last slowly got out the words,"Mr. President, I have forgotten what I was going to say." The poor fellow looked quite over-whelmed, and all the members were so surprised that no one could think of a word to say to cover his confusion. The papers which were read to our little society were not printed, so that I had not the satisfaction of seeing my paper in print; but I believe Dr. Grant noticed my small discovery in his excellent memoir on Flustra.

I was also a member of the Royal Medical Society, and attended pretty regularly; but as the subjects were exclusively medical, I did not much care about them. Much rubbish was talked there, but there were some good speakers, of whom the best was the present Sir J. Kay-Shuttleworth [1804-1877]. Dr. Grant took me occasionally to the meetings of the Wernerian Society [of which Robert Jameson was the founder and president], where various papers on natural history were read, discussed, and afterwards published in the 'Transactions.' I heard Audubon deliver there some interesting discourses on the habits of N. American birds, sneering somewhat unjustly at Waterton [author of Wanderings in South America. By the way, a negro lived in Edinburgh, who had travelled with Waterton, and gained his livelihood by stuffing birds, which he did excellently: he gave me lessons for payment, and I used often to sit with him, for he was a very pleasant and intelligent man.

Mr. Leonard Horner also took me once to a meeting of the Royal Society of Edinburgh, where I saw Sir Walter Scott in the chair as President, and he apologised to the meeting as not feeling fitted for such a position. I looked at him and at the whole scene with some awe and reverence, and I think it was owing to this visit during my youth, and to my having attended the Royal Medical Society, that I felt the honour of being elected a few years ago an honorary member of both these Societies, more than any other similar honour. If I had been told at that time that I should one day have been thus honoured, I declare that I should have thought it as ridiculous and improbable, as if I had been told that I should be elected King of England.

|

|

Robert Jameson (1774–1854) |

During my second year at Edinburgh I attended [Professor Robert] Jameson's lectures on Geology and Zoology, but they were incredibly dull. The sole effect they produced on me was the determination never as long as I lived to read a book on Geology, or in any way to study the science. Yet I feel sure that I was prepared for a philosophical treatment of the subject; for an old Mr. Cotton in Shropshire, who knew a good deal about rocks, had pointed out to me two or three years previously a well-known large erratic boulder in the town of Shrewsbury, called the"bell-stone"; he told me that there was no rock of the same kind nearer than Cumberland or Scotland, and he solemnly assured me that the world would come to an end before any one would be able to explain how this stone came where it now lay. This produced a deep impression on me, and I meditated over this wonderful stone. So that I felt the keenest delight when I first read of the action of icebergs in transporting boulders, and I gloried in the progress of Geology. Equally striking is the fact that I, though now [1876] only sixty-seven years old [at the time of writing this section of the autobiography], heard Professor Jameson [who died in 1854], in a field lecture [while Darwin was a student in Edinburgh] at Salisbury Craigs [some high cliffs outside Edinburgh], discoursing on a trap-dyke, with amygdaloidal margins and the strata indurated [i.e., hardened into stone] on each side, with volcanic rocks all around us, say that it was a fissure filled with sediment from above [Jameson was a Neptunist, a then current theory of geology], adding with a sneer that there were men who maintained that it had been injected from beneath in a molten condition. When I think of this lecture, I do not wonder that I determined never to attend to Geology.

From attending Jameson's lectures, I became acquainted with the curator of the museum, Mr. [William] Macgillivray, who afterwards published a large and excellent book on the birds of Scotland.2 [At this point Darwin's son, Francis, edited out the following comment, which appeared in the orginal manuscript:"He had not much the appearance or manners of the gentleman."] I had much interesting natural-history talk with him, and he was very kind to me. He gave me some rare shells, for I at that time collected marine mollusca, but with no great zeal.

My summer vacations during these two years were wholly given up to amusements, though I always had some book in hand, which I read with interest. During the summer of 1826 I took a long walking tour with two friends with knapsacks on our backs through North Wales. We walked thirty miles most days, including one day the ascent of Snowdon [the highest mountain in Wales]. I also went with my sister [on] a riding tour in North Wales, a servant with saddle-bags carrying our clothes.

The autumns were devoted to shooting chiefly at Mr. [William Mostyn] Owen's [a friend of the family], at Woodhouse, and at my Uncle Jos's, at Maer. My zeal was so great that I used to place my shooting-boots open by my bed-side when I went to bed, so as not to lose half a minute in putting them on in the morning; and on one occasion I reached a distant part of the Maer estate, on the 20th of August for black-game shooting, before I could see: I then toiled on with the gamekeeper the whole day through thick heath and young Scotch firs.

I kept an exact record of every bird which I shot throughout the whole season. One day when shooting at Woodhouse with Captain Owen, the eldest son [William Mostyn-Owen], and Major Hill, his cousin, afterwards Lord Berwick, both of whom I liked very much, I thought myself shamefully used, for every time after I had fired and thought that I had killed a bird, one of the two acted as if loading his gun, and cried out,

And the gamekeeper, perceiving the joke, backed them up. After some hours they told me the joke, but it was no joke to me, for I had shot a large number of birds, but did not know how many, and could not add them to my list, which I used to do by making a knot in a piece of string tied to a button-hole. This my wicked friends had perceived.

How I did enjoy shooting! but I think that I must have been half-consciously ashamed of my zeal, for I tried to persuade myself that shooting was almost an intellectual employment; it required so much skill to judge where to find most game and to hunt the dogs well.

One of my autumnal visits to Maer [Hall] in 1827 was memorable from meeting there Sir J. Mackintosh [the husband of a sister of Josiah Wedgwood's wife's sister], who was the best converser I ever listened to. I heard afterwards with a glow of pride that he had said,"There is something in that young man that interests me." This must have been chiefly due to his perceiving that I listened with much interest to everything which he said, for I was as ignorant as a pig about his subjects of history, politics, and moral philosophy. To hear of praise from an eminent person, though no doubt apt or certain to excite vanity, is, I think, good for a young man, as it helps to keep him in the right course.

|

|

Emma Darwin (1808–1896) |

My visits to Maer during these two or three succeeding years were quite delightful, independently of the autumnal shooting. Life there was perfectly free; the country was very pleasant for walking or riding; and in the evening there was much very agreeable conversation, not so personal as it generally is in large family parties, together with music. In the summer the whole family [including Uncle Jos's daughter, Emma Wedgwood, Darwin's future wife] used often to sit on the steps of the old portico, with the flower-garden in front, and with the steep wooded bank opposite the house reflected in the lake [or mere, for which the estate is named], with here and there a fish rising or a water-bird paddling about. Nothing has left a more vivid picture on my mind than these evenings at Maer. I was also attached to and greatly revered my Uncle Jos; he was silent and reserved, so as to be a rather awful man; but he sometimes talked openly with me. He was the very type of an upright man, with the clearest judgment. I do not believe that any power on earth could have made him swerve an inch from what he considered the right course. I used to apply to him in my mind the well-known ode of Horace, now forgotten by me, in which the words"nec vultus tyranni, etc.,"3 come in.

Notes:

(Works Cited)

1. See: Browne, E. J. 1995. Charles Darwin: Voyaging, vol. 1 London: Jonathan Cape, p. 73. Browne notes that the Plinian was founded by a group of undergraduates in 1823.

2. William Macgillivray (1796-1852), was actually the author of A History of British Birds, a work in five volumes (1837-1852), not of a book on Scottish birds. He was a leading Scottish naturalist, a talented artist, and an expert on birds and a gifted artist. He wrote many scientific papers and books.

3. Horace, Carmina (III, 3, 1):

Justum et tenacem propositi virumNon civium ardor prava jubentium,

Non vultus instantis tyranni,

Mente quatit solida.

"He who is just and resolute will not be changed in purpose by the blind wrath of the people, or by the threats of tyrants."

Most shared on Macroevolution.net:

Human Origins: Are we hybrids?

On the Origins of New Forms of Life

Mammalian Hybrids

Cat-rabbit Hybrids: Fact or fiction?

Famous Biologists

Dog-cow Hybrids

Georges Cuvier: A Biography

Prothero: A Rebuttal

Branches of Biology

Dog-fox Hybrids