Moose-elk Hybrids

Alces alces × Cervus elaphus

Mammalian Hybrids

|

A diligent scholar is like a bee who takes honey from many different flowers and stores it in his hive.

—John Amos Comenius

|

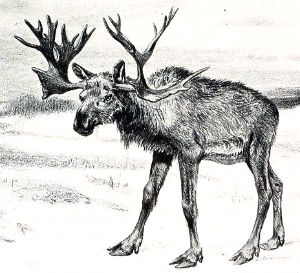

Alces alces

Red Deer (Cervus elaphus), known also as an Elk or Wapiti in North America.

Red Deer (Cervus elaphus), known also as an Elk or Wapiti in North America.

Moose (Alces alces) and elk (Cervus elaphus) come into potential breeding contact in both northern North America and northern Eurasia. And it does seem that moose-elk hybrids occasionally occur, given the existence of photos of obvious hybrids such as those shown above, and the fact that there are reports about such hybrids on record. Thus, a probable moose-elk hybrid, a male with mixed features, was shot in Montana in 1931. A communication appearing in vol. 20 (p. 95) of Science News Letter, and dated August 8, 1931, reads as follows:

* See also: California Fish and Game, 1931, vol. 17, p. 198 (Internet Citations: CALFG); Nature, 128, 676-677 (17 October 1931).

Hybrid variation or individual variation?

It is well known that hybridization produces variation. Ongoing hybridization, especially when the hybrids themselves are capable of producing offspring, creates highly variable populations, typically made up of individuals that are intermediate in various ways between the two parental forms that originally crossed to produce them.

There is, however, a tendency among biologists to describe variation produced by hybridization as “individual variation.” Generally speaking, people who use this term leave hybridization out of account altogether, that is, they conceive of the population in question as pure (unaffected by hybridization) but variable. For example, in the present case Nygrén (2007) interpreted animals with moose-like bodies and deer-like antlers as pure moose with deer-like antlers. Indeed, she uses the term “cervina” to designate the sort of antlers seen on the moose in the slide show at the top of this page. In Latin cervina means “of or pertaining to a deer or stag.” So describing antlers as “cervina” amounts to a fancy way of saying they look like deer antlers.

Typical moose antlers are palmate. Palmate antlers are, at least in part, shaped like a hand, that is, there is a flat region like a palm, around the edges of which tines are attached like fingers. Fallow deer also have palmate antlers.

In her survey of what she called “A. alces” Nygren classified antlers into three categories palmate, cervina, and intermediate (between palmate and cervina). As she conceptualizes the population, it is composed of pure moose that somehow show a range of variation in their antlers from moose-like (palmate) to deer-like (cervina). So there is no discussion of possible hybridization. She summarizes her results as follows:

But how would anyone who did think in terms of hybridization interpret such results? Well, obviously, they would say that “moose” with cervina antlers are really moose-elk hybrids that tend more toward the elk end of the spectrum. They would go on to point out that the facts that such individuals tend to be smaller is consistent with such a hypothesis because elk are smaller than moose. And they would also point out that the higher frequency of cervina antlers toward the south is an independent fact that is also consistent with that notion because elk occur at lower latitudes, on average, than moose, so southern moose populations would be more affected by hybridization with elk than norther populations. As to the shift toward a higher frequency of cervina with age, anyone familiar with hybridization will know that, in many crosses, hybrids at a younger age more resemble one of their parents while coming to resemble the other at a later age. For example, hybrids between the polar bear and the brown bear are white at birth, but take on a yellowish-white or blue-brown coloration as they mature.

A key fact discriminating between the two hypotheses (individual variation vs. hybrid variation) in this case is Nygren’s finding that the frequency of cervina antlers increases toward the south. If the observed variation is due to hybridization this shift is expected because the chance of hybridizing with an elk increases toward the south as elk become more frequent. However, it is inconsistent the supposition the other alternative because in the absence of hybridization the expectation is for the variation to be spatially uniform, that is, cervina antlers would be just as likely to occur in all geographic regions, whether elk were present or not.

In connection with the present cross, Nygren's data is of interest because the high rates of cervina and intermediate antlers in so-called moose populations suggests that hybridization between moose and elk/red deer is extensive.The Stag-moose

Stag-moose (Artist: Robert Bruce Horsfall)

Stag-moose (Artist: Robert Bruce Horsfall)

In addition, an intermediate animal of this type is known from fossils and has been described as a species, the stag-moose (Cervalces scotti), pictured at right. According to Wikipedia, it

Article continues below

A stag-moose skeleton in the Royal Ontario Museum (Image: Wikipedia, Staka)

A stag-moose skeleton in the Royal Ontario Museum (Image: Wikipedia, Staka)

The Illinois State Museum website states that “The stag-moose or elk (scientific name Cervalces scotti) is

Charles Hallock

Charles Hallock

In 1911, sportsman Charles Hallock claimed to have seen a specimen which apparently consisted only of a rack of antlers attached to a frontal bone. From his comments, it is not entirely clear whether the rack was of ancient origin or a modern specimen, but given that he says that he saw it in a region of northwestern Minnesota (Kittson County) where elk and moose regularly come together, it was probably the latter. At any rate, he is quoted in The Pittsburgh Press, (July 16, 1911, p. 5), as follows,

Enlarge

Enlarge