Mary Anning

Biography

EUGENE M. MCCARTHY, PHD

|

| Mary Anning at work (by Henry De la Beche) |

|

Throughout her life, Mary Anning (May 21, 1799 — March 9, 1847) the great fossil hunter, lived in the little seaside town of Lyme Regis on the south coast of England. The simple serendipity of this place of birth, together with the gift of a penetrating eye, would bring her lasting fame.

Mary began her career early. When she was only ten, her father, Richard Anning, died of the combined effects of tuberculosis and a serious fall. He had been a cabinetmaker and carpenter who supplemented his income by collecting fossils — then known as “curiosities” — down on the beach and selling them to tourists. It was he who taught Mary how to find and clean fossils.

In The History and Antiquities of the Borough of Lyme Regis and Charmouth, George Roberts (1834, p. 288) tells how, “after her father's death, Mary Anning went down one day

|

| Blue Lias Cliffs, Lyme Regis. Image: Michael Maggs |

Her regular method of searching was to comb the beaches near Lyme for any fossiliferous rocks that might have fallen from the cliffs along the shore. This was the famous Blue Lias formation, an abundant source of Jurassic ammonites and belemnites, and of the occasional fossil vertebrate as well.

|

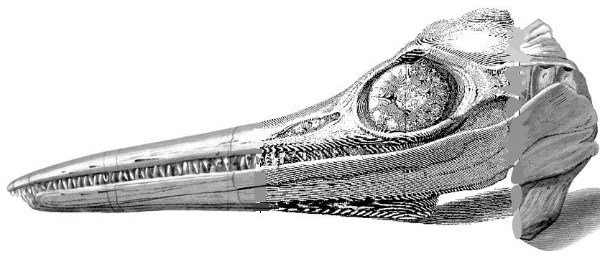

| Head of Anning's first ichthyosaur. Length: 4 ft. (122 cm). Source: Home (1814). |

In 1811, in a block of fallen shale, her brother Joseph found a massive skull (see figure above) that he mistook for a giant crocodile's. It lay mostly hidden beneath the sand. This would have been nothing exceptional — many fossil crocodiles were already known — but Mary went back to investigate, and over a period of months slowly picked away the rock to expose the remainder of the skeleton. She eventually revealed an entire ichthyosaur — the first complete specimen ever discovered. She was just twelve years old at the time.

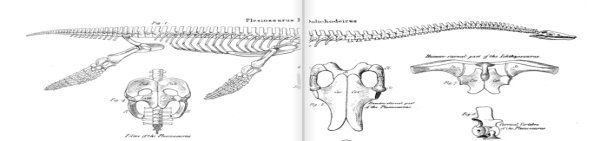

Mary Anning went on to make many other important discoveries, including several

additional well-preserved ichthyosaur skeletons. From a scientific standpoint, however, perhaps her most important find was a largely intact plesiosaur (Plesiosaurus dolichodeirus), which she located in 1824. This “grand fossil skeleton of Lyme-Regis,” with its incredible snakelike neck, was an immediate international sensation. Its illustration from the original description (Conybeare 1824) appears below.

|

|

Anning's plesiosaur: Length about 3 meters (~10 feet). From Conybeare (1824) (Enlarged view) |

Up to that time, plesiosaurs had been poorly known and Georges Cuvier, the celebrated French paleontologist and comparative anatomist, had rejected as fanciful English geologist William Conybeare's initial assertions about the structure of this animal. But when he read Conybeare's description of the intact specimen he admitted he had been wrong and pronounced Anning's fossil a major discovery. Thereafter Anning entered into correspondence with Cuvier and sold him specimens on a regular basis. Adam Sedgwick at Cambridge University also bought many important specimens from Anning.

|

|

Dimorphodon macryonx Credit: David Peters |

Over the years, Anning discovered innumerable additional fossils of scientific value, but a few stand out. In 1828, she found the first pterosaur ever found outside continental Europe, Dimorphodon macryonx (see figure, right), a strange winged creature with a huge head like a toucan's. The next year she discovered a fossil fish, Squaloraja (see picture >>), a weird thing halfway between shark and ray. Then, in 1830, she found a new, large-headed plesiosaur. This she managed to sell for 200 guineas (£210) — at that time, more than a year's income for many people.

Indeed, she made so many discoveries that her finds inspired what was apparently the earliest attempt to reconstruct the appearance of the Mesozoic world. Duria Antiquior (Ancient Dorset), a painting based on Mary Anning's discoveries, by Sir Henry Thomas De la Beche, seems to have been the first pictorial representation of a scene from deep time.

Duria Antiquior (Ancient Devon) by Sir Henry

Thomas De la Beche

In the days when she began her work, few Europeans had any notion of prehistory other than the biblical “darkness” that supposedly preceded the divine creation. What made her discoveries so important to the history of science, then, is that they provided evidence that forced scientists to imagine, like De la Beche, an ancient world very different from our own, and so to begin to think of evolution and how it might occur.

Although she grew up in poverty and lacked a formal education, Anning taught herself so well that she was visited and consulted by many eminent scientists of the era. And in fact, she was the acknowledged expert in the field. Prussian naturalist Ludwig Leichhardt went so far as to dub her the “Princess of Paleontology.” In the end she became the “worthy, Miss Mary Anning, whose name is already well known in every part of the world where persons read of the discoveries and progress of science” (Roberts 1834, p. 284).

The achievement of such fame and expertise was no small feat for a lower-class woman in early nineteenth-century England. As Lady Harriet Silvester (1753-1843) commented in her diary, “the extraordinary thing in this young woman is that...by reading and application

English paleontologist Edward Pigeon (1830, p. 377) gave her high accolades in what was then a man's world, praising “the arduous and zealous exertions of this female fossilist in her laborious and sometimes

Are we hybrids? Many facts suggest it's true!

|

Notes:

—Mary Anning's commercial activities in her seaside hometown of Lyme Regis provided the original inspiration for the tongue twister "She sells sea shells by the seashore."

—In 2010 Mary Anning was included in the Royal Society's list of the ten British women who have most influenced the history of science.

—At the age of 14 months, Mary was struck senseless by lightning in the arms of her nurse, who was killed along with two others by the same blast. This experience, together with a near drowning she experienced in later life, prompted the British academic and lawyer John Robert Kenyon to hail her with a snatch of doggerel verse:

Thee, Mary! first 'twas lightning struck,

And then a water-vat half drowned;

But I can't think 'twas mere blind luck

Twice left for dead-twice brought thee round.

No! Fortune in her prescient mood,

I must believe, e'en then was planning

To fabricate a something good

Of Thee, the twice-saved Mary Anning.

More Reading:

Torrens, H. 1995. Presidential Address: Mary Anning (1799-1847) of Lyme; "the greatest fossilist the world ever knew." British Journal of the History of Science, 28: 257-284.

Works Cited:

Conybeare, W. D. 1824. On the discovery of an almost complete skeleton of the plesiosaurus. Philosophical Transactions of the Geological Society of London, 2nd series, 1: 381-389.

Home, E. 1814. Some Account of the Fossil Remains of an Animal more nearly Allied to Fishes than any of the other Classes of Animals. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London, 104: 571-577.

Pigeon, E. 1830. Fossil remains of the Animal Kingdom. (supplementary volume to the English translation of Cuvier's The Animal Kingdom). London: William Clowes.